Solar power has been a booming business recently, thanks in part to fast declining costs, but more importantly governments that sprinkled it with lavish subsidies. And the curious thing was that the governments that could afford it the least were among the most generous. In 2011, almost a third of global solar capacity installations happened in Italy. Greece also tripled its solar capacity in 2011. It’s a good example how blatantly generous these governments have been at the brink of financial collapse – it was one last crazy party before the fall. And the party is followed by a nasty hangover: as subsidies are lowered, European solar producers shrink their capacities and/or whine about lower demand for their costly products.

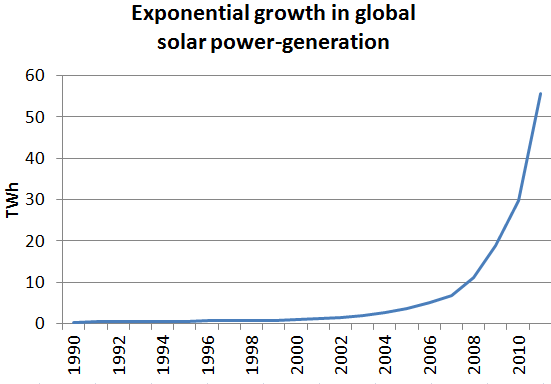

The exponential global growth in solar energy capacities and production in the last decade has been picked up in the blogosphere from BP’s recently released global energy statistics (which is always a goldmine for energy economists). In the following post, I also look at some of the more detailed data to show a last-minute boom in some southern European countries. The subject is also topical because European photovoltaic manufacturers have just attacked their Chinese counterparts that they sell panels below costs.

Global boom and fast declining costs

But first, let’s recap the global tendencies. Yes, global capacity has been booming thanks to generous subsidies (in most cases feed-in tariffs). The current wholesale price of base-load electricity is around 50 EUR/MWh in Europe, while the levelized cost of solar electricity (that is, the cost of electricity needed for new investments to break even) is generally well above 200 EUR/MWh – and solar energy is intermittent and not completely predictable. Someone has to pay the price difference, either consumers or taxpayers.

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2012

The goal of renewables should be to cut CO2 emissions. When you translate the price differential between solar and the current electricity price into CO2 abatement cost (that is, the CO2 prices needed to compensate for the higher electricity cost of solar), you get figures of well over 200 EUR/ton of CO2. Comparing that to the current market price of 7 EUR/ton, and a number of options costing well below 50 EUR/ton, this still looks an extremely expensive way of cutting CO2 emissions.

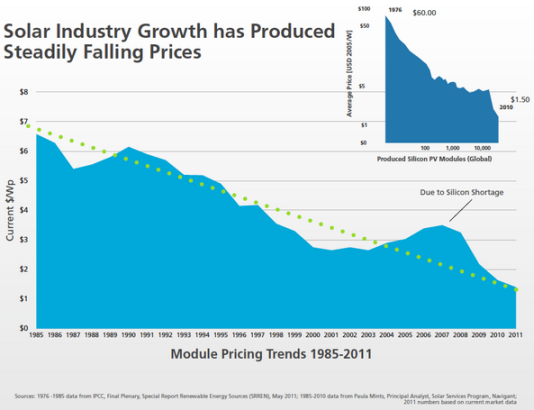

So the main drivers of the photovoltaic industry are still the governments. But the technology has been also improving. There has been a massive cost decline in recent years: current solar panels are more efficient and cost less than a few years ago, not least because the emergence of cheaper suppliers in developing countries, like China. Ironically, amidst the solar boom, many Western solar firms have recently gone bust, because Chinese manufacturers cut under their prices. Now European companies blame that Chinese firms sell below their costs (i.e. the use dumping prices), but others, selling Chinese modules disagree.

Source: Climate progress

If it continues like this, solar may become competitive without subsidies at the wholesale level within a decade. But once you install a capacity, you lock in the then prevailing high prices – investment costs are the bulk of the cost of electricity produced by solar panels. If you built your solar farm three years ago, it cost twice as much than if you build it now. This suggests that it is worth waiting a few more years before jumping on the wagon.

Many advocates of the technology say that in order to get the cost reductions, you need all these huge subsidies promoting production: first you have to subsidize the industry, so that it could grow bigger and more efficient. Up till now I have not seen any confirmations of this ‘infant industry’ or learning-by-doing theory. On the contrary, even during the 90’s, with much less subsidies and slower growth rates, solar panel prices decreased around the same rate as since the subsidy-boom began. (Panel prices halved during the 90’s, then again halved until 2011, while solar generation grew 10% annually between 1990-2001, but over 45% annually[!] between 2001-2011.)

The steady growth before the subsidizations started suggests that the price of solar would have declined very similarly had there been no such grand-scale support schemes (but of course this cannot be easily verified). Putting the money into R&D is certainly a more efficient means to lower costs than to subsidize actual production.

Waiting is valuable, especially when ‘grid parity’ gets close

Much of the solar PV is small-scale (rooftop) installations. With the fall in price of solar modules, the cost of solar PV has been getting closer and closer to retail electricity prices in some places, like Italy or Germany (what is generally labeled ‘grid parity’ in the jargon). Once you reach a level where you do not need to subsidize rooftop installations any more, the game changes dramatically. This point was actually brought forward by retail prices raised by high subsidization of renewables. In Germany, for example the subsidy element is the same order of magnitude as the wholesale price itself. (For those interested, I give a bit more detailed account of grid parity at the end of the post.)

When costs decline so fast and a tipping point is just around the corner, it is best not to rush to build up wholesale photovoltaic capacity fast and lock in extreme sums of quasi-public spending.

Italy, Greece did not have time to wait

The history of solar power has been dotted with periods of extraordinary booms in certain countries for a couple of years. That is in part because of the fast changing costs: if the regulation (of subsidies) lags, it may provide investors with sky-high returns. Government bureaucrats are usually not up-to date regarding PV cost declines – investing in the subsidized sector was sometimes case of “regulatory arbitrage” (if you are very generous) or “state capture” (if you are not). Germany in the early 2000’s, Spain before the financial crisis are two eminent examples, with well over 100% annual growth rates for 5 years.

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2012

One could think that with the raging financial crisis, debt-problem Southern European countries already cut back their renewables subsidies and growth in 2011.

Well, not exactly. Italy was the biggest market worldwide for solar PV last year, almost a third (31.6%) of global solar installations taking place there. In a single year, more than 9 GW of capacity was built there, almost quadrupling the installed capacity. This is equivalent to the capacity of 8-9 large scale nuclear blocks, but of course the average utilization of solar panels is only around 20-25%. The cost was around EUR 20 bn or likely more.

Maybe even more surprisingly, Greece also pumped up its solar program, with installed capacity tripling to 600 MW, probably costing more than EUR 1 bn.

Those are the costs estimated from ‘normal’ installation costs (around 1.5 USD/W module cost, plus around the same in other installation costs). Actual cost figures are probably much higher, considering that so much capacity had to be built in a single year, creating bottlenecks in the supply chain. The limited number of service providers must have made fortunes on the boom. So did those well connected enough to get permits fast.

Speed was of the essence – everyone suspected that the good times will not last much longer amid the financialcrisis. Indeed, by this year the subsidies on new installations have been cut significantly, for example in Italy. But last year, because of the sky-high feed in tariffs, it was still worth to install the capacities at very high costs. But exactly the high cost of the tariff system to the respective governments made it clear that the system is not sustainable, and the more investors rush in, the less so. You needed to be fast, to be among the first, and who cares about building it cheap.

The fast buildup of solar capacity in crisis hit countries tells more about their political economy than about their energy sector. We already knew that these governments are not very good stewards of their spending (that is why they are in a crisis), and this was no different in the case of solar industry. And some people made a lot of money out of that.

The Münchhausen trick: Grid parity

When the grid parity is reached depends on the cost of installation as well as three important factors: the retail electricity price level, the amount of sunshine a place gets and the rate of return required for the project. If you want to do some calculations, here is a useful website.

But here is a twist: the level of retail prices depends crucially on how much the consumers pay to subsidize previously installed renewables. So as the previously installed wholesale renewables push up the retail price, consumers will increasingly opt out, make their own solar installations, and make those wholesale capacities to some extent redundant.

Germany, for example already pays huge amounts, the electricity bills include a 35 EUR/MWh ‘surcharge’ to subsidize renewables, the same order of magnitude as the wholesale price. Thus, high prior renewables spending has brought forward the point when reaching the grid parity becomes a reality (like in the tale of Münchhausen, who supposedly pulled himself out of a swamp by his own hair). For example, in Germany and Italy, this is starting to happen now. In the case of Germany, a generally low interest rate environment helps as well (but not any more in the case of Italy).

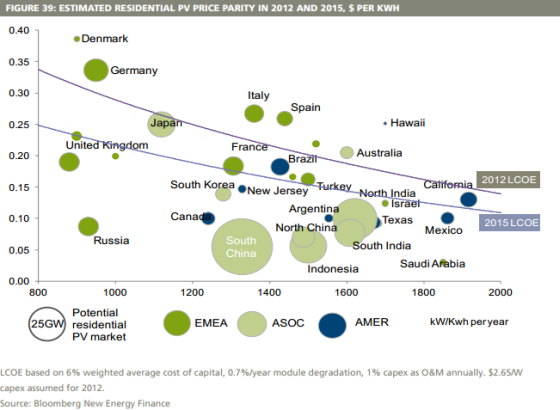

The following chart from Bloomberg New Energy Finance suggests that already in 2012, and at 6% capital cost, new residential PV requires no more subsidies in Germany, Italy and Spain (On the horizontal axis it measures solar radiation, and on the vertical axis, the retail price of electricity. In any country above the 2012 line, which represents current costs, it is worth installing solar PV).

source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

The high retail price in Germany, Italy and Spain is a result of high renewables subsidization, and probably also due to the low level of competition in the retail electricity markets. As PV brings new competition, retail prices will likely decline. In particular, this might be the case in Germany, where there are many who can afford to invest from their own savings, and do not need credit – and in that case a 6% or even higher relatively safe return could be attractive.

A bejegyzés trackback címe:

Kommentek:

A hozzászólások a vonatkozó jogszabályok értelmében felhasználói tartalomnak minősülnek, értük a szolgáltatás technikai üzemeltetője semmilyen felelősséget nem vállal, azokat nem ellenőrzi. Kifogás esetén forduljon a blog szerkesztőjéhez. Részletek a Felhasználási feltételekben és az adatvédelmi tájékoztatóban.