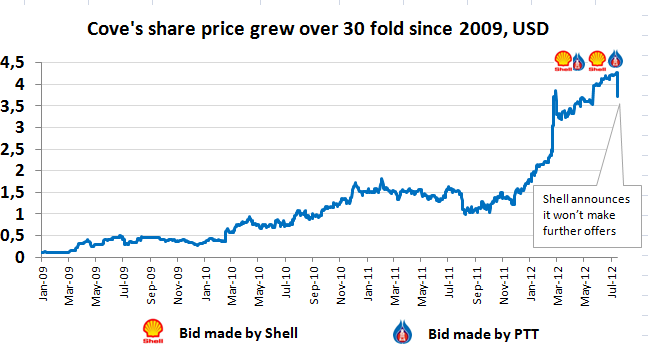

Buy ambitious experts from majors, distressed assets from small companies and have lots of luck. This was the recipe of COVE Energy, a junior that started exploring oil and gas only three years ago. It increased its market capitalization over 700-fold and recently was a subject of a bidding war. The major prize is its 8.5% stake in an offshore Mozambique prospect, which is likely to hold gas equivalent to two to four times the European Union’s annual gas consumption.

By Réka Sarolta Torma

Overnight success

Cove Energy was established in 2003 as a mineral exploration company with no oil and gas activity at all. It decided to diversify its focus with oil and gas exploration only in 2009 and hired highly experienced professionals – with African connections – from large competitors (i.e. Shell and BP). Note the irony that Shell is one of the bidders for the company now.

Cove’s strategy was to take advantage of the financial crisis and acquire minority interest in the underexplored regions from other small players with financial difficulties. In 2009 Cove acquired assets in Mozambique and Tanzania for only USD 11 million. In the following year these assets yielded in world class discoveries: Rovuma Area 1 (where Cove Energy has 8.5% stake) offshore Mozambique, operated by large US independent oil and gas exploration and production company Anadarko, is estimated to hold enough gas to support up to 50 mn tons per year Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) capacity. The likely size of the recoverable resources equals two to four times the annual gas consumption of the EU. Furthermore, Cove has minority interest in other promising assets in Mozambique (onshore and offshore) and Kenya (offshore).

East Africa: new frontier opened up by independents

Oil and gas companies are continuously seeking underexplored areas with significant hydrocarbon potential. The exploration phase requires expertise and is generally less capital intensive but more risky (geologically) than production. Therefore it is often smaller players (juniors) who open up new upstream (exploration and production of crude oil and natural gas) frontiers, while it takes longer for large independent oil and gas players and the majors (the six largest private sector owned oil companies in the world) to take note, as they are focusing on high impact activity. East Africa was forgotten by upstream industry until some smaller junior players (e.g. Tullow Oil, Ophir, Maurel & Prom) and one or two larger but more adventurous independents (like Anadarko) entered the Eastern part of the continent. Some important onshore oil and offshore gas discoveries have attracted larger players (Apache, BG, Eni, Statoil), most of whom have also made significant finds since. Eni’s discovery in Area 4 of Rovuma basin competes in size with Anadarko’s (and Cove’s) find in Area 1 in the same basin.

Although currently there is lack of infrastructure and marketing options both onshore and offshore, the volume of gas already found offshore suggests that East Africa shall become a major LNG supplier of Asia by the end of the decade. Despite all these discoveries, East Africa is still relatively underexplored, and therefore attracts numerous new entrants.

Two, completely different bidders for Cove Energy: Shell and PTT

East Africa with its huge natural gas potential is considered as one of the next big things in LNG, and Cove’s access to the East African story attracts great attention. Since February 2012, the most serious contenders for Cove have been two players with very different backgrounds and motivations.

Shell wants a presence in East Africa

Anglo-Dutch super major Shell - which made two offers since February - (among many other things) develops industry leading LNG technologies and seeks access to the East African LNG industry. Shell owns more LNG capacity than any other big international oil company. It has liquefaction plants in Australia, Brunei, Malaysia, Nigeria, Oman, Russia and Qatar. In 2011 its joint ventures supplied more than 30 percent of global LNG volumes.

PTT wants to expand globally

PTT, the Thai National Oil Company (NOC , i.e. a state controlled firm), - who outbid Shell two times since February - seeks to satisfy Thailand’s future demand for LNG as natural gas is becoming a growing part of the country’s energy mix. In recent years NOCs have become increasingly important players in the upstream M&A market. Their home countries are booming, and securing adequate supply for the growing energy needs is of key importance. Moreover, due to their state backing, NOCs have a strong balance sheet and are less price sensitive. In the past two years the Chinese NOCs, together with the Korean National Oil Company (KNOC) and PTT accounted for more than 18% of global Upstream M&A deal value. In 2010 they invested over USD 90 billion, outspending the Majors by USD 16 billion. Chinese Sinopec and CNOOC were the biggest spenders, but KNOC significantly stepped up and PTT entered North America through a transformational deal in the Canadian oil sands.

Probable winner: PTT – hard to beat a determined NOC

Since Shell made the first offer, the bids were climbing up, but Cove’s share price was getting even higher, as shareholders – Cove is 75% held by investment funds – were betting on even better offers. Shell’s first bid (USD 1.56 bn) already included a premium of 27%, but was outbid by PTT. Shell’s second offer was USD 1.8 bn. PTT’s second counterbid is the highest offer to date, valuing Cove at USD 1.9 bn: 184% of the pre-bidding war share price. Interestingly, a few days ago the actual share price was still 10% higher than the highest offer so far. This means that Cove Energy’s shareholders had been expecting a higher bid. As Shell announced on July 16 that it wouldn’t revise its offer, now PTT is the likely winner. At the moment of the announcement, Cove shares fell slightly below the level of PTT’s offer, which is also the consensus of analysts’ price targets (Bloomberg, 12-month forward looking). Both Shell and PTT’s offer is valid till July 25.

This is another example of state-backed companies outbidding privately owned companies for resources. Of course they may be overpaying. A recent study (see the NBER research paper or a blog summary here) found that winners of bidding wars tend to suffer as their share prices underperform shares of non-winners by 50% on average for the next three years. In case of state owned companies it is even harder to find out in retrospect whether an acquisition made economic sense. The bottom line is that there are fortunes to be made by enterprising small upstream firms in new areas.