Good wine doesn’t necessarily take… a barrel. At least not always. Rolling Barrel exclusive summer edition. Because we said right from the start that we wouldn’t only write about energy…

I tasted a few wines produced in amphorae during a trip to Georgia. Wine, but not as we know it… The technology is actually very old (Georgia is a contender for calling itself the ancestral home of winemaking), and has generally remained unchanged since the era of the Argonauts. Which may not be a surprise considering how a lot of things in Georgia seem to have a tendency to remain unchanged. The infrastructure, for example, is… timeless. Maybe built by the Romans, but definitely no younger than the 1970s, except for a few showcase projects in the capital.

Timeless Georgia… Photograph by the author

Timeless Georgia… Photograph by the author

This timeless nature isn’t necessarily a problem when it comes to winemaking. Over the past few years, many people have rediscovered so-called vin naturelle, or natural wine (of which Georgian amphora-based wines are a subtype). Jancis Robinson, the Financial Times’ wine critic, often writes about this movement and is generally enthusiastic about it. A number of books were also published in the topic (here, here and here). London and France now boast their own wine bars with only natural wine on the list. Natural wine is becoming fashionable in Hungary as well (even if there are debates about its exact definition); Terroir Club, Kézműves Borok (Hand-made Wines) and Pinceáron webshops have all followed this trend. In fact, a lot of smaller producers in Hungary and the region are actually pretty close to “natural” winemaking, without necessarily realizing it…

As in all cults, there are serious debates with regards to what is acceptable (and what isn’t) during “natural” grape cultivation and winemaking. There is a basic agreement that adding yeast or any nitrogen-rich yeast nutrient is taboo. But can you, say, add sulfur during bottling? Wine in its natural form already contains a little sulfur… Should you go for organic, biodynamic, or just regular grape cultivation, or is it enough if the winemaking itself is “natural”? Are temperature-controlled steel tanks OK? How about filtering and fining? I won’t go into all the details now for the sake of brevity.

Before EU funds existed...Source: brooksonwine.com

Before EU funds existed...Source: brooksonwine.com

Maceration: the longer, the better

Natural winemaking is becoming popular also thanks to the (re)discovery of wine’s positive health effects. (Which was common knowledge in Hippocrates’ time.) And natural wines may be even better from this viewpoint.

It seems these health effects are attributable to the phenols and polyphenols (which make up the plant’s natural immune system) which are released from grapes’ skins during winemaking; but this dissolution takes time, of which there is plenty during natural winemaking, but which may be limited during accelerated industrial winemaking processes. (If you are interested in more details, you can start at the usual place.) So it’s best to look for wines with long maceration periods, not just as a means to protect yourself from free radicals, but because of their fine taste – a fortunate coincidence. Although if you’re not used to this taste, you may need some time to get accustomed to it…

Source: torbwine.com

It’s got soul

These wines aren’t easily accessible; they’ve got soul and need caring attention. But some people have quite a taste for them – myself included. Well-bodied, with an incessant change in flavor and scent during tasting – these wines are often like roller-coasters. And not everyone likes roller-coasters. But it certainly helps you understand why people wrote odes to wines...

A light white wine, Georgian style. Photograph by the author

A light white wine, Georgian style. Photograph by the author

But back to amphora wines… The technology itself is very simple: the completely mature grape bunches are squashed by foot, poured into amphorae dug into the ground, capped after fermenting, and – if some special occasion calls for it – opened the next summer at the earliest, to skim the finished wine from the grape bunches accumulated at the bottom of the amphora. In some Georgian villages, they actually leave the wine untouched for several years, but even there that’s only meant for hardcore fans; tourists are usually offered wines left to macerate for only 9 months. To compare, wines left on the skin for a mere 6 weeks are usually considered very well-bodied and heavy, whereas most “industrial” red wines are only left for a few days, enough for some of the pigments to dissolve and give the wine its color, but not much else. Nowadays, the majority of white wines are not left on the skin at all (with some exceptions in Burgundy), whereas in Georgia (and in ancient times) this same long maceration was used for both red and white wines.

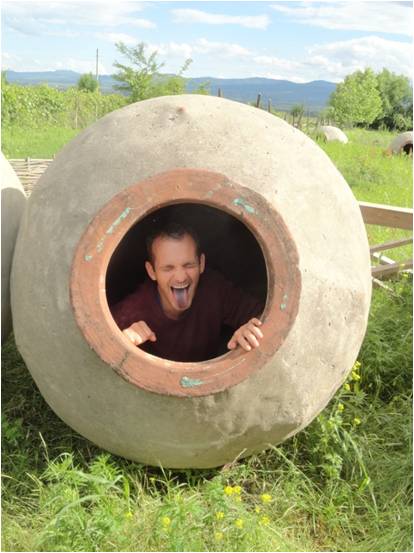

Economist and amphora. Early 21st century

Economist and amphora. Early 21st century

And where can you find Hungary’s first amphora-produced wine? That is, first since the Romans… I don’t know the answer for sure, but I did make one myself. And, just to have a “control group”, I made a barrel-produced version as well – you can find the description in the box below. I couldn’t have done this without my parents’ help (from transporting the wine to the daily punching down the cap during fermentation), for which I’m very grateful – they are also enthusiastic readers of the blog, by the way. And if anyone’s heard of another amphora-produced wine in Hungary, let us know (we do know that Croatia produces some) - we haven’t seen any in stores. Tokajicum announced plans to make such a wine, but there hasn’t been any trace of it as far as we know…

The right kind of bitter taste

I’m sure everyone’s biased towards their own wine, so this is just a brief description. Kékfrankos (Blaufrankisch) isn’t my favorite type of grape, but buying organic grapes is very cumbersome, so I didn’t have any other choice. Neither did I regret it – the ingredients were of very good quality, and that’s the key. I really liked both the barrel and the amphora-made end products. It has the usual roller-coaster flavors, it’s complex, it hits you hard. (And that’s not because of the alcohol content – just 12% – but because of the dissolved extracts.) The tannins are strong, though they have softened since the initial phase; and – what’s more important – they’re not raw, which tends to be a problem in Hungary sometimes. The amphora-made version is the same, but at another level altogether. It’s a strong, slow-drinking wine, with even more extracts and undercurrents of the beeswax I used to line the amphorae. Both have a pleasing fruity scent, and a distinguished liqueur-like, bitter taste from the mid-sip.

The end result…

The end result…

The best part is that you don’t actually need to do too much, just oversee a process that basically worked the same way in Paleolithic times, and let nature’s own bacteria and fungal yeasts work their magic…

How did I make wine in an amphora? Minimalist style

First off, I read a lot of online articles and several books* on winemaking, so that I’d have a general picture of the technology itself (both regular winemaking and natural wines). This doesn’t guarantee success in itself; you need both luck and a sense of intuition as well as practical experience. My first serious** attempt was successful, although they say this is true of most amateur winemakers… I got the amphorae though the Légli Ceramic Manufacture, and purchased the Kékfrankos (Blaufrakisch) grapes from a certified organic producer near Szekszárd in southern Hungary. Squashing by foot, fermenting in an amphora/vat, and all the rest. I didn’t use any additives; I pressed, let it settle and racked the wine after macerating it for around 2 and 9 months, respectively. It was neither filtered nor fined. I hesitated with regards to adding sulfur (which serves several purposes, including protecting the wine against oxidation). In the end, I decided not to add any. No harm has come from it so far; in fact, the wine remains good for a relatively long time (days) after opening the bottle, which suggests its own antioxidants are quite strong. We’ll have to wait several years and see if it can last in this way in the longer run. But given the interest my wine has generated, I may never find out…

*The books: Bird: Understanding Wine Technology, Feiring: Naked Wine, Goode/Harrop: Authentic Wine. Johnson/Robinson’s World Atlas of Wine provides a good overview of both traditional and industrial technologies, though its focus is on the (excellent) descriptions of the world’s winemaking regions.

**My critics say this is my second try at winemaking, though I don’t consider last year’s attempt a serious one :-) Besides, that was neither amphora, nor barrel-based wine.

A bejegyzés trackback címe:

Kommentek:

A hozzászólások a vonatkozó jogszabályok értelmében felhasználói tartalomnak minősülnek, értük a szolgáltatás technikai üzemeltetője semmilyen felelősséget nem vállal, azokat nem ellenőrzi. Kifogás esetén forduljon a blog szerkesztőjéhez. Részletek a Felhasználási feltételekben és az adatvédelmi tájékoztatóban.