We always suspected that Russia was taking unconventional gas more seriously than it said it did. Now the government, even if at low level, is talking about the risks to Gazprom. In this piece we are looking at the potential political consequences of unconventional gas.

The relative political strength of the US will increase, and Russia’s will decline as a result of unconventional gas. The EU will, as usual, first ban things and then catch up. In the Middle East, the relative power of the more conservative oil exporters would increase, at the expense of Qatar that has become an active political player recently. Gas transportation will be more market driven and less politicized. Gas supply security will remain lower on the political agenda – at least in countries with access to multiple sources.

In our previous piece we covered the economic impacts of the gas becoming more abundant and relatively cheap. In this part we go through some of the potential political consequences. We have already touched upon a few of these in the previous parts: for example, that a gas OPEC has become less likely, or that LNG exports in the US face some political hurdles.

We have also hinted at the countries that are likely to win out from the unconventional gas supply side revolution. These are countries that can attract capital to large infrastructure and/or gas production projects. These countries tend to be rich and well organized (or China). The EU should also be in this group, but it typically first introduces regulatory restrictions, then after a decade it realizes that it is losing out to other countries and introduces a grandly named program (how about “Energy Agenda 2025”?) to do away with those restrictions. So eventually it should benefit too. But in the next 10 years the US is likely to keep a competitive advantage of everything energy intensive versus Europe. Currently, we estimate that the excess natural gas bill in the EU amounts to about 1% of GDP (the alternative scenario is that gas costs the current US level in the EU as well).

Despite joining the unconventional party with a considerable delay, the emergence of more sources (and decreased demand) has already led to more competition and lower prices in Western Europe. This has put supply security issues lower on the political agenda (after peaking in the wake of the 2009 Russian gas supply crisis). Central and Eastern Europe, meanwhile, with more dependence on Russian supplies and not many alternative sources, could only partly benefit from the increased competition in the western part of the continent. Here, still more infrastructure would be needed to fully benefit from cheaper gas. And because supply security has become less of an issue for influential Western European politicians, it will be more difficult to convince them to pay for infrastructure in Central and Eastern Europe on a large scale.

Ukraine’s gas import bill is around 6% of GDP, it would love to have some unconventional gas

Ukraine, where the gas import bill is around 6% of GDP, does have domestic shale gas resources, and could benefit directly if it manages to exploit those. For that, it needs to get its business environment in order though, which is not straightforward. Even countries with no unconventional gas deposits can benefit if global gas prices decline. The biggest beneficiaries would be Russia’s ex-Soviet neighbours. In many of these countries, the gas import bill is in excess of 5% of GDP, and in Moldova it is around 16% of official GDP at the new prices it has to pay since the end of 2011. But again, to get the cheaper gas, these countries would need to build up alternative infrastructure and would have to have a reasonable business environment, which is the biggest hurdle for most of them.

If gas is cheap, it would replace some of the (incremental) coal demand in China and India. These countries currently consume 49% and 8% of global coal production, respectively, and their energy needs will grow fast in the next 20 years. The world would be a hugely better place if they used lot cleaner gas instead of coal, both for the local population and global CO2 emissions. So emerging country lungs will be clear winners from cheaper gas. The political consequence of that may be that some key emerging countries will be somewhat more ready to agree to climate deals and CO2 reductions, but this process would also take time.

And the losers are...

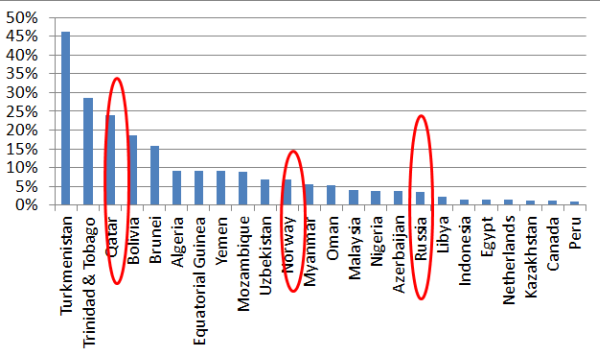

But who is going to lose from unconventional gas? The important thing to decide here is if the unconventional gas is going to be cheaper than the conventional one. That is possible in the long run, and the consequences would be even more serious. But in the near term that is a tall order as the conventional gas can be also very cheap to produce. Nevertheless the excess supply from the unconventional gas globally depresses gas export prices, and therefore the “rent” that traditional gas producers can earn above production costs. How severe the blow of lower gas prices mean to a country also depends on the importance of gas export revenues compared to the country’s GDP. This is shown in the chart below.

Value of net gas exports as % of total GDP (in 2011), assuming USD 8/MMBtu average selling price

*We left out East Timor, where gas export revenues vastly outstrip non-energy GDP

Source: BP, IMF, CIA, own calculations

Cheaper export gas prices would be a problem for some of the smaller countries like Turkmenistan and Bolivia. Algeria’s political thaw could be brought forward by cheaper gas, pushing towards a catch-up with its neighbours (Tunisia and Libya)

Top gas exporters: Qatar, Norway...

In terms of absolute quantity, the top three exporters are circled on the chart. Qatar would clearly be a different force if gas becomes cheaper. Currently the country is playing an increasing political role in the Middle East-North Africa region, mostly supporting regime change. If for the moment we assume a broadly unchanged oil price, then the relative standing of the conservative Gulf countries, led by Saudi Arabia, would increase. The coverage from the Al-Jazeera news channel, also supported by the Qatari state, would deteriorate, and it would have to report on more touchy subjects like domestic disturbances…

Norway (and the Netherlands, the fourth largest net exporter) already sell some of their gas at spot(cheaper) prices. So overall cheaper gas would cause some problems - like a decline in the pace of the asset build-up of the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund… But we would predict no revolution in either countries – and no big regional or global impact from cheaper gas either.

Iran: taking away the carrot

Iran could well be among the top gas exporters, yet its gas balance is slightly negative. Iran shares the huge South Pars/North Dome field with Qatar. This field has something like 50 trillion cubic meters of gas, or about 16 years worth of world consumption. Even Iran’s recoverable share would be worth several years of world consumption, and it has other reserves as well. The reason why it cannot monetize this huge revenue source is that it cannot attract the technology, investment and marketing opportunities, due to the international embargo in place. But as long as gas prices are relatively high, this is a potential reward for the country: normalize your relationship with the rest of the world, and you will be able to export gas. That incentive was not enough to tip the balance in the past, but would be even less of an incentive in the future is gas globally becomes cheaper. So cheap gas will make it even less likely that Iran would give up its nuclear weapons efforts.

Russia: in a squeeze

Russia traditionally have been using export gas prices as a diplomatic tool for in mainly what it calls its “near abroad” and also to subsidize low domestic prices. But so far it did not get much state revenue directly out of it. That is changing. Russia's sales prices to FSU countries are no longer that low: in 2011 the average Gazprom FSU sales price was USD 266/ thousand m3, while the average “Far abroad” sales price was $313/thousand m3. This is not much of a difference and the gap is continuing to close. The average domestic sales price was still low at $93/thousand cubic meters, but that is also set to increase. And Russia is in a dilemma: should it wean its domestic economy off cheap gas, if there is a chance that global gas prices converge to its current domestic prices (in the US gas prices are already around that level or even lower)?

At the current rate of natural gas extraction tax, the revenues from it are less than 1% of GDP. The political focus is mainly on gas, but the main revenue earner is oil. There is an intention to increase tax revenues from gas – the natural gas extraction tax have been increasing steeply in the past few years, to $19 per thousand cubic meters now, and it is slated to increase further to above $30/tcm in 2015. Clearly there is a need for government revenue from every possible source: President Putin both promised a lot of goodies before his re-election (about 4% of GDP worth), and wants to balance the budget by 2015. And the oil price that would balance the budget is already USD 120/bbl, even before all the spending increases went through.

So Russia will tax gas more, and it will be able to use it less as a political tool in ex-soviet countries as it needs to concentrate more on revenues even there. Until the economic crisis and even shortly after it, Russia had thought that it can more or less set both prices and quantities in Europe, and even that it can tailor prices to individual countries. It has become increasingly clear that it has to choose, and it chose more or less maintaining quantities sold and gave price discounts. It may have to face even harsher choices if unconventional gas gains ground in Europe and the economic depression reduces demand there further. No wonder that Russia, true to its traditional deep concerns over the environment, is greatly worried about the potential effect of fracking on European water resources. But at the same times decided to use fracking technology in Siberia for unconventional oil…

Russia wants to maintain some kind of long-term gas price indexation to oil, but spot prices increasingly have an impact on gas pricing. There are likely to be long-term gas contracts in the future as well, but the pricing will increasingly be spot based. And lower than Russia hoped for: gas is no longer more or less equivalent to oil in price, and probably it will not be, apart from short periods. The revenues from exporting gas are likely to decline from the current 3.5% of GDP. China is a potential escape route, but it will not buy pipeline gas at anything close to oil indexed prices…

Russia’s political, economic and military influence will be waning abroad because of its fiscal squeeze, and sooner or later it is set to have its own “Russian Spring” at home, in some form or another. But these processes would be only expedited and strengthened by cheap gas, not caused by it…

Pipeline politics: thing of the past?

More plentiful and more evenly distributed gas undermines the rationale of expensive, long-distance pipeline infrastructure projects. Gas may become available closer to home, and when not, probably LNG is a better way to transport it in most of the cases. Hopefully the global gas market would become less politicized and more like the oil market right now: hugely important, but very difficult to drive by political decisions (just look at how difficult it is to shut Iran out of the international oil market even by concerted efforts). But pipelines are such a large topic that they will merit a separate post…

Trans-Alaska source: Alaska-in-Pictures.com

A bejegyzés trackback címe:

Kommentek:

A hozzászólások a vonatkozó jogszabályok értelmében felhasználói tartalomnak minősülnek, értük a szolgáltatás technikai üzemeltetője semmilyen felelősséget nem vállal, azokat nem ellenőrzi. Kifogás esetén forduljon a blog szerkesztőjéhez. Részletek a Felhasználási feltételekben és az adatvédelmi tájékoztatóban.