A pipeline project is made of steel and political stability along its route. Both of these things got scarcer and more expensive in the past 10 years, while the alternatives became more abundant. Nabucco seemed to be a good idea 10 years ago. But then the world changed.

The Nabucco gas pipeline seemed such a good idea when it was conceived, in 2002. Back then, it seemed to make a lot of economic sense. In the previous 10 years, EU gas consumption had increased by 45% (it was the period of “Dash for Gas”), and the projections were equally optimistic. The 2002 edition of the World Energy Outlook forecasted a 33% increase of gas consumption in OECD Europe between 2000 and 2010, and a further 25% between 2010 and 2020. European sources were running out, so imports were set to increase even faster. There was a serious discussion whether Russia would be capable of meeting the higher European import demand – and the political consequence of increased dependency if the answer was yes. There was no question about gas prices being linked to the price of oil in Europe, and steel prices (needed for pipelines) were 50% lower than today (well, China was yet to have its building boom).

There were political arguments too. The EU, and also the US wanted to make Europe and the ex-Soviet states less dependent on Russia. Turkey was a strong US ally in the region, soon to start its EU accession negotiations.

The perfect solutions to all these problems seemed to be a pipeline that ships gas from Azerbaijan and from some nebulous other places to Austria. The idea of the Nabucco was born.

To summarize, Nabucco was supposed to be:

- A solution for the increasing gas deficit in Europe

- Commercially attractive for participants while…

- …providing a cheaper source for European countries

- Diversification of European gas sources, away from Russia

- A Western outlet for Azerbaijan gas exports, thus…

- Linking Azerbaijan (and Turkey) economically and politically to the West (as opposed to Russia)

I've a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore…

Let’s fast forward to today. The world has changed a lot (this is just a brief sketch of the numerous changes, please follow the links to read our earlier, more detailed accounts of pieces of the story).

First, it became obvious during the recent crisis that political or economic stability in any given country, even within the EU, cannot be taken for granted. Governments and regimes are violently overthrown, retrospectively change conditions or just simply go bankrupt. Tough times result in tough governments and higher political and economic risks for any project, especially ones with a long payback period and immovable assets. Second, the economic landscape has changed dramatically: European gas demand is lower, and there is more supply than had been expected ten years ago.

Opera: The incredible shrinking Nabucco

Opera: The incredible shrinking Nabucco

The outlook for European gas demand has worsened along with the economy. The increase in the 11 years to 2011 was only 10% (2010 was a very cold winter in Europe, but even then, gas consumption was up only by 20% compared to 2000) . And the economic stagnation makes projections a lot less optimistic as well. The 2012 World Energy Outlook forecasts a 3% European gas consumption increase between 2010 and 2020 and even that looks increasingly unrealistic. Our guess is that the International Energy Agency will revise European gas demand forecasts further down, and we may well see an outright decline in European demand.

Several things started to eat into natural gas demand in the past ten years. Gas is mainly used for two purposes: electricity generation and heating. In electricity generation, renewables became a sizeable force in Europe in the past 10 years, partially displacing gas demand. In addition, cheap gas in the US depressed coal prices there and internationally. This resulted in coal displacing (the still relatively expensive) gas in Europe in recent years. Greenery also means better insulation and thus less gas consumption for heating. And a slower growth trajectory means less demand increase, if at all, in industry.

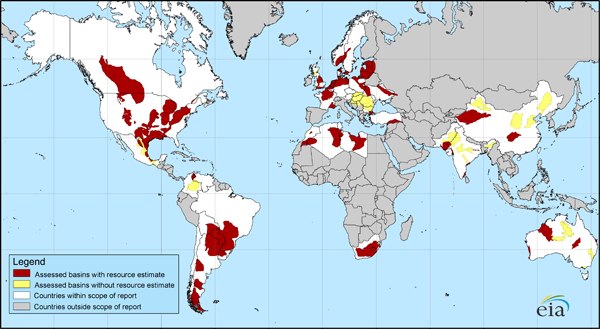

On the supply side the changes have been even more dramatic. Gas now seems to be everywhere. There is unconventional gas in the US (some of it may be exported soon) and conventional discoveries in East Africa, the Levant and many other places. There is even a prospect of increased European gas production, despite the political resistance, from unconventional sources. Importantly, a lot of these potential new sources are at more convenient places than Azerbaijan.

There is shale gas outside the US. Source: EIA.

There is shale gas outside the US. Source: EIA.

Nabucco was meant against the Russians. But given the demand and supply changes, the unilateral dependence on Russian gas supplies is much less of a threat than it used to be. Increasingly the Russians also admit this, even though they do not give up any of their market power without a fight.

The LNG alternative for Europe

Global gas abundance without transport infrastructure is not very useful, but in this area there has been a quiet revolution over the last 10 years as well. Europe built up a tremendous amount of LNG import and gas storage capacity and LNG import terminal building and expansion are still ongoing. If we count those under construction, EU countries have an LNG import capacity that amounts to 2/3 of their total imports – and about 7 times the originally proposed maximum capacity of Nabucco. , At the extreme, if the EU used all its LNG import capacity to the full, plus Norwegian and North African imports, it could stop importing Russian pipeline gas altogether. That would be unfeasible in practice at the moment - the EU would need to take 2/3 of all global LNG flows, as opposed to the current less than 1/3. But it gives an idea of how significant European LNG import capacities are now. And also gives an idea how much room there is for additional competitive LNG export projects…

LNG is a less politicized form of gas transportation than relying on a few pipelines, and that is exactly why it looks more attractive than pipelines. Most of the LNG volumes are still transported on the basis of bilateral contracts, but an increasing proportion of trade is available on a spot basis. If one provider cuts supplies for whatever reasons, importers can easily substitute it with another. The same goes for importers – there is a lot less mutual dependency (and blackmail potential) than in the case of pipelines. When political stability is in shorter supply globally, this is a very useful feature. Pipelines are like the public broadcast systems – centralized and regulated, and vulnerable to disturbances. LNG trade is like the Internet – decentralized and robust.

When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?

Escalating costs, potential political and economic instability along the supply route, the emergence of additional gas resources elsewhere and LNG import infrastructure in Europe all argue against Nabucco, and there is not a factor that went in its favor. Oh, and did we mention that because of the economic crisis, capital for risky projects also got scarcer and more expensive? To us, the project does not look like a good investment. But that is just our private opinion.

A bejegyzés trackback címe:

Kommentek:

A hozzászólások a vonatkozó jogszabályok értelmében felhasználói tartalomnak minősülnek, értük a szolgáltatás technikai üzemeltetője semmilyen felelősséget nem vállal, azokat nem ellenőrzi. Kifogás esetén forduljon a blog szerkesztőjéhez. Részletek a Felhasználási feltételekben és az adatvédelmi tájékoztatóban.